Transplantation of the first pig kidneys in legally dead humans: The pig-heart controversy has been raised since Bennett’s birth

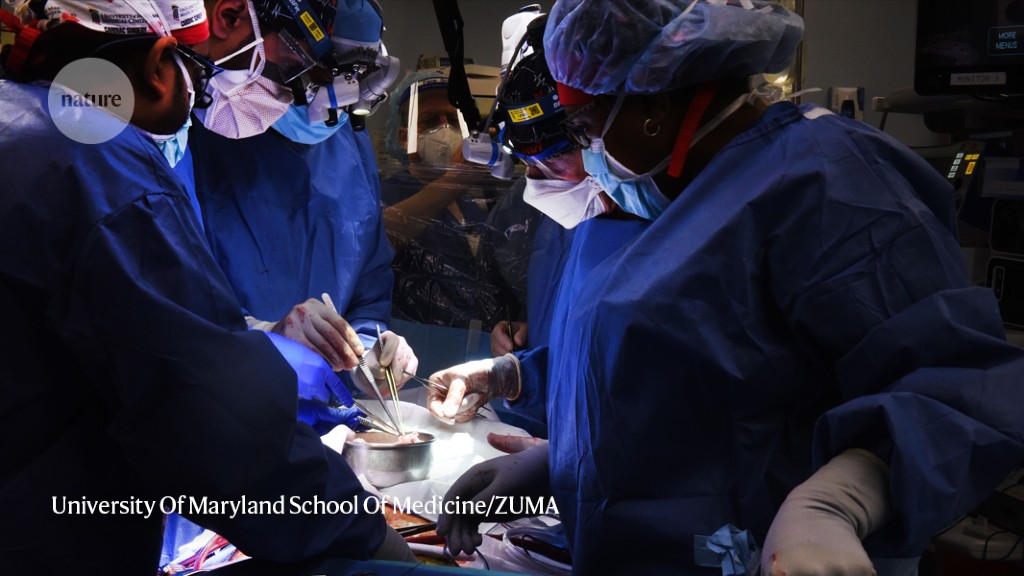

In January, Bennett’s doctors offered him the chance to receive a heart from a pig. He took it. He said in a release that it was his last choice and that he knew it was a shot in the dark. On 7 January, doctors transplanted the heart, which had been genetically modified so that the human body would tolerate it.

It was just one of several cases of xenotransplantation that made the news this year. A few months after Bennett’s procedure, two research groups2,3 independently reported transplanting the first pig kidneys into three people who had been declared legally dead because they lacked brain function. The trials found that the organs produced urine and were not rejected by the human immune system, even two to three days after the procedure. Surgeons performed two more pig-heart transplants in brain-dead people in June and July.

Clinical trials, researchers argue, are needed to answer questions such as the best type of pig to use and how to ensure the animals are not carrying infections. “I think we need to take that step forward and go to the clinic,” says Wayne Hawthorne, a transplant surgeon at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Bennett’s transplant and subsequent death brought unprecedented public attention to the topic — but it also exposed the risks. Researchers see the need to move cautiously. “If there’s a problem, you could set the whole field back,” Hawthorne says.

Despite the differences, some research teams say they’ve been asked by the FDA to provide more data on how pig organs fare in non-human primates. “It’s like saying a drug suggests it will do what we want in humans but won’t in monkeys — but let’s still test it in monkeys,” says Cooper. It is completely illogical to be doing that. The FDA did not state how much primate data was needed for specific cases, but provided guidance saying that primate models would not be enough to prove pig organs are safe for humans.

The teams have used different approaches. MakanaTherapeutics, based in Miami, Florida, modified three genes in its pigs. The changes in these genes all prevent human antibodies from attacking an organ, and they show the most evidence of improving organ survival in non-human primates, says company founder Joe Tector. He says that as genetic engineering gets better, it will be easier to talk about changing or adding genes.

Eckhard Wolf, a molecular biologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany, agrees. He says their general strategy is to keep it simple. His team has engineered five genetic modifications into a wild breed of mini pig from New Zealand, and the first litter was born in September. These mini pigs are similar in size to humans, so they don’t need a modification to grow bigger. If all goes well when his team transplants the mini-pig hearts into baboons, Wolf says, the European Medicines Agency, which regulates drugs and medical products, could approve small human trials of hearts within three years.

The trials in living people should be the best way to find out whether the transplant is a success or a failure. Keeping brain-dead individuals on life support for this long could be considered unethical, says Jayme Locke, a transplant surgeon at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who led the other team that transplanted a kidney this year into a brain-dead person2. Locke is working towards applying to the FDA for permission to start clinical trials using kidneys from the same Revivicor pigs as used for Bennett’s heart. Her team has already listed one such trial in a federal registry, although it is not yet approved and has yet to begin recruiting the 20 patients who would receive the kidneys.

Hawthorne is now planning a clinical trial of the pig islet cells in people who have a severe form of type 1 diabetes that causes blood sugar to drop extremely suddenly. If the funding is found, trials could begin within a year. Several groups have found pig islet cells to be safe in humans.

One of the biggest concerns for regulators is the spread of diseases in pigs. There are several ways this could cause problems, but it is not clear how much.

Then there are porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs), viral elements embedded in the pig genome. Pieces of inherited viral DNA do not get picked up from the environment. They are harmless to pigs, but some studies disagree if they would be harmful to people or the pig organ. It doesn’t know if it’s a real concern or a hypothetical.

The Harvard Medical School in Boston,Massachusetts, where the work was performed, used CRISPR to scramble all known PERVs in the pig genome in order to determine whether it was possible to inactivate these viral elements.

And although Fishman says it’s unlikely, viruses that infect the two species could recombine in the human body to create a new pathogen, much as influenza viruses do in birds, bats and pigs.

Still, Mohiuddin can’t rule out that the virus played a part. Revivicor pigs were tested for CMV and had been found to be free of the disease. Mohiuddin and others suspect that the virus was latent in the organ and would have been detectable only by testing the animal’s antibodies. Revivicor didn’t want to say how many pathogens it screens for, but it said it had developed more sensitive CMV tests.

The eGenesis is planning for more complex organs. It hopes to begin testing pig livers within 12 to 18 months. Three to six people close to death would each be put into a pig’s stomach to remove toxic waste from their organs. Curtis says the company is also working on juvenile pig hearts that would similarly serve as a bridge for children with heart problems until they can get a human heart transplant.

Tector says that there is a lot they have to answer. 70% of Makana’s baboons live for more than a year with a functioning pig kidney, meaning the company is ready to start clinical trials. It applied to the FDA earlier this year.

Fishman says the most important thing when trials begin is to collect as much data as possible from each participant. “We owe it to the patient, and we owe it to society.”

A Poor Man’s Strangeness During a Heart Transplant: Why a Strange Patient Almost Gives His Heart to a Pig

The night before the transplant, he didn’t sleep well. When he woke up around 3 am he forgot to place his mug under the coffee machine and the coffee ended up on the floor.

The very unusual operation he was about to perform in the morning of January 7 became just like a heart transplant, since he arrived in the operating room. The pig is the organ donor. The man is suffering from a failing heart.