Climate Change and the First United Nations Climate Summit in Africa: Why the Middle-Income Countries are Off Track and How They’ve Been Done

As the United Nations climate conference opens in Egypt, the most critical talks will likely focus on the soaring costs of limiting — and adapting to — global warming, especially in the world’s most vulnerable countries. It’s a contentious conversation more than a decade in the making.

The first climate summit in Africa in two years is happening. African countries are faced with some of the worst impacts of climate change and many diplomats hope the African COP will be focused on that.

It is the group’s desire that a dedicated financial facility be created to pay nations that are already facing the effects of climate change at the summit.

The researchers think that nations are off track. Poorer countries have failed to meet a promised goal of givingclimate finance to vulnerable nations. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICS) were expecting multilateral organizations such as the World Bank to increase funding to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and make communities and ecosystems less vulnerable to climate change, but this has not yet materialized into concrete agreements, Shoukry wrote.

Industrialized nations still haven’t delivered on a longstanding pledge to provide $100 billion a year by 2020 to help developing countries adapt to climate change and to cut emissions in order to limit further warming, or what’s known as climate mitigation. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development says that 93 percent of the money given to developing countries in 2020 went to projects that didn’t adapt.

We can’t afford a COP that’s all talk. The climate crisis has resulted in inevitable loss and damage and delayed much-needed development, as well as pushing our adaptation limits.

Sarr defended the U.N. conference as “one of the few spaces where our nations come together to hold countries accountable for historical responsibility” and pointed to the success of the 2015 conference in Paris in setting the goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 F).

Poor countries are under pressure from rich countries to come up with money to cut global emissions, according to the Climate Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that works with governments.

And they are dramatic ones, droughts in Africa and floods in Pakistan, in places that could least afford it. For the first time in 30 years of climate negotiations, the summit “should focus its attention on the severe climate impacts we’re already seeing,” said World Resources International’s David Waskow.

Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, wrote in a foreword to the report that political will was needed to increase adaptation investments and outcomes.

We need to be ahead of the game if we want to not spend the coming decades in emergency response mode.

The World is Far From Its Goal: Reducing Carbon Monoxide Emissions, Coping with the Heat, and Adapting to Climate Change

The UN published the report days before its annual climate conference starts in Egypt. In a separate report published last week, the UN said the world isn’t cutting greenhouse gas emissions nearly enough to avoid potentially catastrophic sea level rise and other global dangers.

“But you can also meet the adaptation needs, even more so than you already are, if the discourse is raised significantly, the level of ambition, so that you can actually continue to work on Mitigation even more,” says Mafalda Duarte, CEO of Climate Investment Funds.

Yet most of the financing that’s being doled out is going to projects like wind and solar farms that are aimed at limiting further increases in global temperatures. That left a huge shortfall for projects like building flood defenses or introducing crops that can help poorer nations deal with warming that’s already happened.

Now, rampant inflation and an energy crisis caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine could complicate efforts to convince developed nations to make good on their financial commitments. It’s not necessary to increase future obligations in line with the trillions of dollars that developing countries will actually need to prepare for a hotter Earth.

It’s important to change our mindset and think differently when it comes to climate because an investment in another place is a domestic investment.

This is a raging debate, even within the conference. At an event in London this week, young climate activist, and media sensation of last year’s conference, Greta Thunberg stated that The COPs are not working, and she will not attend this year. “The COPs are mainly used as an opportunity for leaders and people in power to get attention, using many different kinds of greenwashing,” Thunberg said.

In short, the world is way off track from its goal of cutting the pollution that drives climate change. Collectively, nations have promised to cut their emissions by about 3% by 2030. But the science shows emissions need to fall dramatically faster – 45% by 2030. That’s to limit warming to the goal set by the Paris climate agreement: 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. About 2.7 degrees is what it’s been for a while.

The money is supposed to go toward new and improved infrastructure that might help keep people safe in a warming world. That looks like a city that’s better at beating the heat and communities that are less likely to be wiped out by a wildfire. Or it could mean expanded warning systems that are able to warn about floods or storm headed their way. The cost of adapting to climate change in developing countries is set to reach over $300 billion per year by the end of the decade, and so there is a push for more funding this year. When it comes to dealing with climate change, what it means to live is different from place to place and the people most affected are not always included in planning tables.

Climate protests are part of the heart and soul of the annual negotiations. In previous years activists have held marches, hunger strikes, sit-ins and other forms of civil disobedience to stress the urgency of the climate crisis.

That plan was met with criticism because of the way it will be financed: carbon credits, which allow companies to pay for someone else to cut their planet-warming emissions, instead of cutting their own.

Sharm el-Sheikh is the location for the conference. As a result, there’s one more elephant in the room at this year’s UN Climate Conference: Egypt’s crackdown on climate protests — and dissenting voices more broadly. Dozens of people have been arrested in the days leading up to the climate conference in an effort to quell protests, which has resulted in tens of thousands of other political prisoners being held in Egypt.

The US is not the only country that hasn’t been able to meet their climate commitments. The United Kingdom has so far failed to deliver more than $300 million it promised last year in international climate finance, a year after that government hosted COP26.

There are some bright spots. Australia, led by a newly progressive government, doubled its planned cut to 43 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2030. A handful of other countries, including Chile, which is working to enshrine the rights of nature into its constitution, have already promised more cuts or say they will soon. But most of those updates are from smaller polluters, or from those, like Australia, that are playing catch-up after previously submitting goals that were egregiously lacking in detail or ambition. “A lot of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked,” Jansen says.

Other wins have put them on the path to making good on their promises. Fransen points to the United States, where the recent Inflation Reduction Act was a huge step towards meeting its 50 percent emissions reduction pledge. But the US still isn’t on track to reach that commitment. Further upping the ante on its goals this year would “strain credibility,” she says, given the nation’s political gridlock.

Fransen is one of the people in the business of keeping track of all those emissions plans and whether countries are sticking to them. It is difficult to take stock. Measuring how much carbon nations emit is something that it means. It involves showing the climate effects of emissions for ten, 20, or 100 years from now.

It is difficult to determine how much CO2 is being produced and whether or not nations are adhering to their pledges. That’s because the gas is all over the atmosphere, muddying the origin of each signal. There are natural processes that release carbon like decaying vegetation and thaw permafrost. Think of it like trying to find a water leak in a swimming pool. If you see carbon dioxide from space, it’s not always certain that it’s from the nearest human emissions, but if you point satellites at Earth, it’s possible. That is the reason why we need more sophisticated methods. A proxy for the emissions beinglched from power plants is possible if Climate Trace can train computers to identify steam billowing from them. Some scientists have been using weather stations to monitor emissions.

The leaders of wealthy countries are warned by the Egyptian hosts of the climate conference that they cannot backpedal on their commitments made a year ago.

Mahmoud Sakr, president of the Egyptian Academy of Scientific Research and Technology in Cairo, says that scientists from climate-vulnerable countries will be urging COP delegates to boost research funding. He suggests that the Middle East and North Africa should have more of their own climate studies because of the arid conditions there. The Arab world is the only place in which less than 1% of published climate studies are from.

In 2015, Egypt estimated that it needs to set aside $73 billion for projects to help the country mitigate climate change and adapt its infrastructure. The minister says that this number has tripled to $246 billion. Most of the climate actions we have implemented have been from the national budget.

However, the LMIC cause was boosted when the phrase “losses and damages” featured in the latest report on climate impacts, adaptation and vulnerability from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published in February. Christopher Trisos is an environmental scientist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and a lead author of the chapter on climate impacts in Africa.

Ian Mitchell, a researcher with think tank the Center for Global Development in London, warned of possible unintended consequences if agreement on loss and damage becomes a deal-breaker at the meeting. High-income countries could agree to the principle and then absorb loss-and-damage finance as part of their humanitarian-aid spending — meaning it would not be new money.

Adil Najam, who studies international climate diplomacy at Boston University in Massachusetts, thinks it is unlikely that these issues will be resolved in Egypt, and says that the politics will probably get messy. He says that despite the high-income countries avoiding loss-and-damage finance it can no longer be avoided as the climate impacts in vulnerable countries are becoming more severe.

Fouad says that organizing this year’s COP in Africa has been transformative. We expect more attention to issues that are important and relevant to Africans, for example food security, desertification, natural disasters and water scarcity. This COP is a chance for more African youth, non-governmental and civil-society organizations to be heard.”

“The challenge is going to be, how do we maintain momentum when there are so many short-term crises and pressures, and yet the climate crisis is intensifying?” says Amar Bhattacharya, who is part of an independent group of experts that was convened ahead of COP27 to advise conference leaders on how to increase climate financing.

Climate Finance Access and Deployment in the 21st Century: Reconciling the United States’ Debt with the World’s Richest Countries

The richest countries received a combined $83.3 billion from the public and private sectors in 2020.

Critics say adding to the debt burden of governments already on shaky financial footing is one of the reasons why the majority of the money is being delivered through loans.

Mia Amor Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, has said developing nations should at least have access to loans on the same favorable terms that were offered to their counterparts in the developed world.

Mottley said during the United Nations in September that they had incurred debts for climate and COVID to fight the inflationary crisis. When others had longer maturities to repay their money, the developing world should seek to find it within seven to 10 years.

As an alternative, there are calls to provide more climate financing in the form of grants, which don’t have to be repaid, says Gaia Larsen, director of climate finance access and deployment at the World Resources Institute’s Sustainable Finance Center.

“[Hopefully], going forward, there will be means of making sure that countries are able to act on climate and that they’re able to do so without further getting themselves into trouble in terms of their debt levels and their ability to pay for all the things they need to pay for,” Larsen says.

Some impacts from climate change are irreversible, according to the UN, and even if countries could immediately stop emitting greenhouse gasses, the effects of global warming would still be felt for decades.

Meanwhile, it can be “tricky” for the most vulnerable countries to access funding, Larsen says. Data and expertise are needed to show how climate funding would be used and how it would benefit the climate in some developing countries.

The United States was among the largest economies that pledged at the UN conference in 2009, to collectively mobilize at least $100 billion every year to international climate aid by 2020.

The special presidential envoy for climate change, John Kerry, suggested that President Obama’s goal could be at risk if midterm elections went the way of the Democrats.

“Simply put, we developed countries need to make good on the finance goals that we have set,” Kerry said in October at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington, D.C.

But observers say those goals are just a drop in the bucket. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, has said emerging economies will need at least $1 trillion a year to eliminate or offset their carbon emissions.

What is the stake at the UN Conference of the Parties? Recent developments in the world after the 2001 Russian invasion and the need of fossil fuels

The rhetoric of the $100 billion is not what I expect from the COP, because it is centered around real results.

The conference of the parties is called a meeting by the United Nations. The Conference of the Parties meeting is known as COP 27 and it is often referred to.

There were some big changes in the world after that. The Russian invasion of Ukraine will loom over this year’s meeting. The invasion further complicated relationships between the world’s largest economies, and upended global fossil fuel markets. One immediate effect of the war is multiple countries including China have increased their short-term reliance on coal-fired power plants, which are the most intense global source of greenhouse gas emissions.

There have been positive developments as well. Renewable energy, such as wind and solar, is growing rapidly. The International Energy Agency predicts that global demand for all types of fossil fuels will peak by the mid-2030s.

Two of the largest emitters, China and India, plan to increase emissions until 2030. They’ve argued that their growing economies need the support of fossil fuels, as other wealthier countries have historically done.

International climate scientists finished publishing the most comprehensive climate science report ever earlier this year. It catalogued the ways in which climate change is affecting everyday lives around the world, because the Earth is already about 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) hotter than it was in the late 1800s.

But limiting emissions could avoid some of the most extreme impacts, like much more deadly heat waves, more flooding in coastal cities due to sea level rise and the loss of almost all coral reefs.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/11/07/1132796190/faq-whats-at-stake-at-the-cop27-global-climate-negotiations

World is on a highway to climate hell: U.S. and Egypt’s prime minister, Muhammad Sharif, and the other 20 richest nations

They argue that wealthier nations should pay for the problems they caused, including the cultural losses that happen when towns and villages must relocate. It has been agreed by wealthier countries to keep talking, but they have yet to commit to new funding.

It’s going to require huge investments. There’s no way to get around it. There’s a lot of money that could be made from eliminating emissions from the global economy. And experts say the cost of not dealing with this problem could be ruinous.

In the United States alone, quickly cutting carbon emissions could grow the country’s economy by $3 trillion over the next 50 years, says Deloitte, the consulting firm. On the other hand, not doing enough to respond to climate change could cost the U.S. $14.5 trillion over the same period.

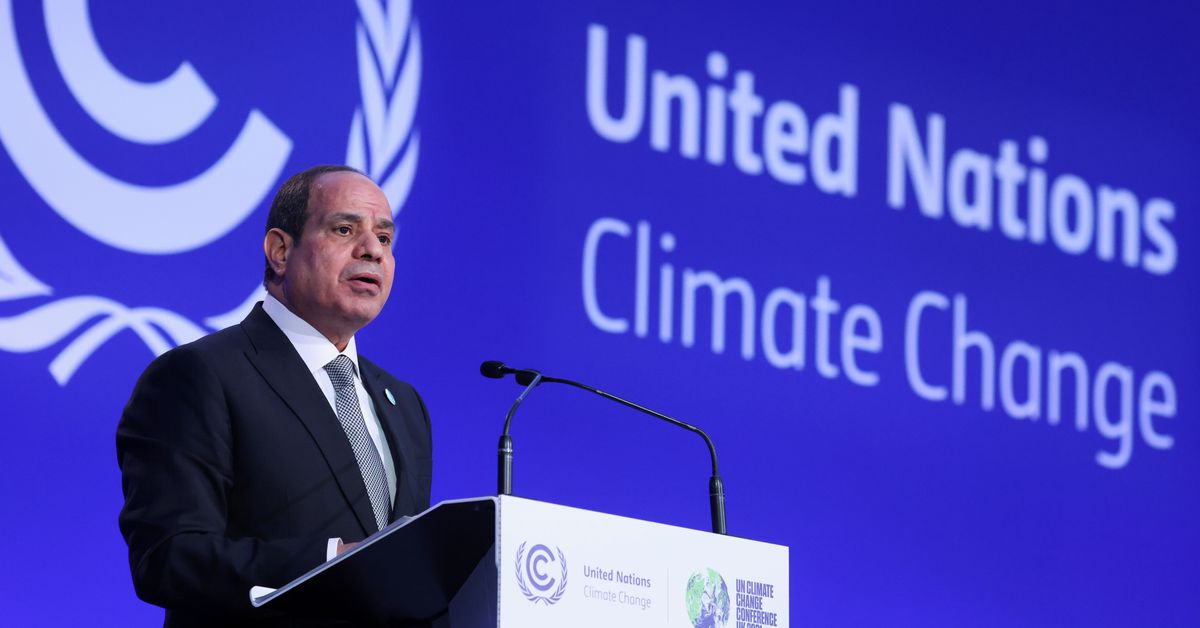

SHARM EL-SHEIKH, Egypt — “Cooperate or perish,” the United Nations chief told dozens of leaders gathered Monday for international climate talks, warning them that the world is “on a highway to climate hell” and urging the two biggest polluting countries, China and the United States, to work together to avert it.

More than 100 world leaders will speak over the next few days at the gathering in Egypt. Much of the focus will be on national leaders telling their stories of being devastated by climate disasters, culminating Tuesday with a speech by Pakistan Prime Minister Muhammad Sharif, whose country’s summer floods caused at least $40 billion in damage and displaced millions of people.

El-Sisi, who called for an end to the Russia-Ukraine war, was gentle compared to a fiery United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, who said the world “is on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator.”

He wants a new pact between rich and poor countries to make bigger cuts in emissions with financial help and to stop using coal in rich nations by 2040. He called on the two largest economies in the world, the US and China, to work together on climate.

Most of the leaders are meeting Monday and Tuesday, just as the United States has a potentially policy-shifting midterm election. Then the leaders of the world’s 20 wealthiest nations will have their powerful-only club confab in Bali in Indonesia days later.

The prime minister initially decided not to negotiate, but Boris Johnson’s plans to come changed his mind. New King Charles III, a longtime environment advocate, won’t attend because of his new role. And Russia’s leader Vladimir Putin, whose invasion of Ukraine created energy chaos that reverberates in the world of climate negotiations, won’t be here.

“There are big climate summits and little climate summits and this was never expected to be a big one,” said Climate Advisers CEO Nigel Purvis, a former U.S. negotiator.

“We always want more” leaders, United Nations climate chief Simon Stiell said in a Sunday news conference. “But I believe there is sufficient (leadership) right now for us to have a very productive outcome.”

The negotiations include speeches by leaders, as well as roundtable discussions that will generate some very powerful insights.

The Status of Climate Change and the Action Plan of the World’s Poorest Countries, as Confirmed by Adow of Powershift Africa

“The historical polluters who caused climate change are not showing up,” said Mohammed Adow of Power Shift Africa. Africa is the most vulnerable to the issue of climate change as it is the least responsible, and it is providing leadership.

Nigeria’s Environment Minister Mohammed Abdullahi called for wealthy nations to show “positive and affirmative” commitments to help countries hardest hit by climate change. “Our priority is to be aggressive when it comes to climate funding to mitigate the challenges of loss and damage,” he said.

“We can’t discount an entire continent that has over a billion people living here and has some of the most severe impacts,” Waskow said. It’s pretty clear that Africa is at risk.

Leaders come “to share the progress they’ve made at home and to accelerate action,” Purvis said. He said Biden has a lot to share after the passage of the first major climate legislation and $375 billion in spending.

There were dire warnings about global disasters and pleas to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as the new international climate negotiations got under way.

There is a chance the world’s population will officially hit 8 billion people during this meeting. When baby 8-billion is old enough to ask, “what did you do for our world, and for our planet, when you had the chance?”, will we answer that question?

What Happened Today at the U.N. s-cop27 Climate Negotiations: A Prime Minister’s Address in Barbados

More than half the world is not covered by multi-hazard early warning systems, which collect data about disaster risk, monitor and forecast hazardous weather and send out emergency alerts.

The new plan calls for $3.1 billion to set up early-warning systems over the next five years in places that don’t already have them, beginning with the poorest and most vulnerable countries and regions. More money will be needed to maintain the warning systems longer-term.

In her opening speech the Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Amor Mottley, went one step further. She called out corporations that profit in our fossil-fuel intensive economy, including oil and gas companies themselves.

She said that corporations should help pay for the costs associated with sea level rise, hurricanes, heat waves and droughts around the world and in countries like hers that don’t have enough money to protect themselves from climate change.

The U.S. government is working with AT&T, a telecommunications company, to provide free access to data about the country’s future climate risks. The idea is to help community leaders better understand and prepare for local dangers from more extreme weather.

Information about temperature, precipitation, wind and the like will be provided first by the climate risk and resilience portal. There will be more risks in the near future, such as wildfire and flooding.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/11/07/1134696214/heres-what-happened-today-at-the-u-n-s-cop27-climate-negotiations

U.S. actions to fight climate change: the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership (FCOP27) conference summary and press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre

More than two dozen countries have pledged to work together to stop and reverse land degradation in order to fight climate change.

The European Union and 26 other countries comprise the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership, which is chaired by the United States.

More than 140 countries agreed at COP26 last year in Glasgow to conserve forests and other ecosystems. However, the U.N. said on Monday that not enough money is being spent to preserve forests, which capture and store carbon.

It is something that Biden has raised repeatedly in speeches to other world leaders, including during the United Nations General Assembly in September.

When Biden speaks about U.S. efforts to cut carbon emissions at the UN climate summit, COP27, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt on Friday, Biden will reiterate that he wants to “help the most vulnerable build resilience to climate impacts,” White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters.

It is not clear whether the president will be able to meet the goal he has for if Republicans gain some ground this week in the mid-term elections.

The United States is the world’s largest economy and largest cumulative emitter of greenhouse gas pollution. China emits more pollution per year than any other nation, but over time it has done more to warm the planet.

The United States has to report on its progress on its climate goals to the United Nations every two years. The Trump administration did not file those reports for 2018 or 2020.

The U.S. Economy in the Light of Biden’s 2002 Budget – A Keystone to a Greatest Successes for the United States

Compared to the other countries involved, the U.S. invests a lot of money in terms of total dollars, but a comparatively small amount relative to the size of its economy.

The administration has two main sources of funds it hopes to draw from: appropriated funding from Congress, and money from federal development agencies.

Administration officials hope the second half will come from sources like the Export-Import Bank and the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), government agencies that use financial instruments like loans and insurance to advance U.S. policy goals abroad.

It remains to be seen if Biden will get his full international goal approved by Congress, as senators at COP27 told CNN they expect the congress to approve a government spending bill by the end of the year.

The president made a promise to raise development finance money for the purpose of meeting the White House’s budget request. It is roughly five times what Congress has done in the past.

The international Green Fund and other means of providing support to transitioning economies are things Whitehouse would like to get a lot of support for. The Republican opposition is driven by the fossil fuel industry.

And since the budget was released in the spring, the headwinds facing the administration have only gotten stronger. Some economists worry that interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve could lead to a recession because inflation has remained persistently high.

How Government Development Agencies Can Help Meet Biden’s Climate Change Efforts: A Case Study of the Import-Export Bank, DFC, and Export-Import Bank

Government development agencies are another source of money for Biden’s pledge. The government invests in foreign projects through agencies, such as the Export-Import Bank, which lend out money and look to generate a return on their investments.

The Export-Import Bank and DFC support their work largely through the fees and returns they make on their loans and other programs, rather than through money they receive from Congress.

It’s possible that these agencies could scale up their spending on climate-focused programs to help meet the president’s pledge, according to Bella Tonkonogy of the Climate Policy Initiative, a nonprofit policy research organization.

But Tonkonogy warned that it isn’t just about whether the government can find the money. The agencies may be unable to quickly identify and vet quality projects.

To work differently, it will have to include developing comprehensive climate strategies, staff capacity, and partnering with other agencies.

President Joe Biden arrives Friday at the UN’s COP27 summit in Egypt with a climate change victory in-hand: a massive US law passed this year that experts have told CNN will go far to help transition the country to renewable energy.

Democrats’ Inflation Reduction Act contained $370 billion for climate and clean energy tax credits and new programs – the largest climate-related investment in the country’s history and a significant statement that the US is back in the clean-energy race.

But that law left out an important thing: international climate finance – funds to help poorer countries adapt to the climate crisis and grow their economies without becoming dependent on fossil fuel.

How can the US get a better deal with climate finance? A challenge facing the midterm elections in the U.S., Germany, and UK

Democratic majorities in the US Senate are already razor thin, meaning Republicans will have significant input on appropriations. And all are watching to see whether the balance of power in Congress could change after a competitive midterm election.

A senior administration official said that while a new budget bill could pass before a new Congress takes control in January, the potentially shifting politics around the midterms puts big question mark how control of Congress could impact US climate finance in the coming years.

The US could walk the talk this year on its domestic climate goals, but it could still face questions about whether it can actually meet its global finance commitments.

It is not limited to the U.S. and other developed nations. It’s also about what the U.S. does for developing countries to help them along,” said Barry Rabe, Professor of Environmental Policy at University of Michigan. It’s a big challenge for Biden to explain how the IRA will benefit other countries.

Private sector buying power may be able to help the US meet its goals. Kerry announced a plan to raise cash for climate action by selling carbon credits to companies who want to offset their emissions.

Kerry said in an interview with CNN that it is one of the few ways that we are able to raise money for the clean energy transition.

“We desperately need money,” Kerry told CNN. It takes trillions and no government that I know of is willing to put them into this every year.

A recent report from the governments of Canada, Germany, and the UK released ahead of COP27 found that overall, the world’s 39 richest countries are failing to meet the annual $100-billion pledge they announced in 2009. But the report noted that there has been some progress, and they are expected to meet it by next year.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development reported earlier this year that the nations raised $82 billion towards the goal in 2020.

Climate officials from Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom said they would meet the $100 billion goal by 2023.

Climate officials acknowledged a lack of trust from developing countries in the ability of developed nations to meet their commitments.

“It does very much remain the case that developed countries and indeed the whole of the global financial system, need to be doing even more and faster, to support developing nations,” Sharma said. It’s all about regaining trust in the system.

There is a dispute over the conference’s goal. Wealthy countries want to focus on ways to help developing nations phase out fossil fuels and transition to renewable energy.

Reply to the Comment by Abdallah El Fattah on Climate Change and Democracy: Implications for Egypt, Syria, and the Middle East

While world leaders are in Sharm el Sheikh to highlight Egypt’s abysmal human rights record a growing number of Egyptians are calling for protests. The demonstrations are likely to be out of the question given that the el- sissi government has banned all demonstrations and criminalized free assembly.

Mr. Biden is also buoyed by a surprisingly strong showing of his party in Tuesday’s midterm elections, a performance that bucked historical trends and may allow the Democrats to retain control of Congress.

Paul Bledsoe, a climate adviser under President Bill Clinton who now lectures at American University, said there was no way Mr. Biden would embrace the idea of loss and damage payments.

He said that America is culturally incapable of meaningful fixes to their problems. There is little to no chance they will be seriously considered regarding climate impacts to foreign countries as a result of not being made to Native Americans or African Americans. It’s a complete nonstarter in our domestic politics.”

John Kerry, Mr. Biden’s climate envoy, has proposed instead to let corporations invest in renewable-energy projects in developing countries that would allow them to claim the resulting cuts in greenhouse gases against their own climate goals. Those so-called carbon offset initiatives are viewed skeptically by many climate scientists and activists, who see them as simply allowing companies to continue polluting.

Before addressing the gathering, Mr. Biden is scheduled to meet with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt and is expected to raise the case of Alaa Abd El Fattah, an Egyptian dissident whose hunger strike in prison has loomed over the summit. On Sunday, Mr. El Fattah promised to stop drinking water during the COP 27 summit. Representatives of nongovernmental groups have threatened to walk out of the conference if he dies.