Climate Change, Adaptation and the Future: Why is the world more interested in disasters than we do now, than tomorrow? A report by Dr Vikki Thompson

Multiple world leaders voiced their frustration that wealthy countries, including the United States, are not paying enough for the costs of climate change. At these talks, developing countries are pushing for compensation for the damages from extreme storms and rising seas, what’s known as “loss and damage.”

The unequal consequences of global warming are “something that’s been talked about quite qualitatively before”, says Dr Vikki Thompson, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol, UK, but this analysis has “managed to really quantify it”. It also includes parts of the world that are often excluded from studies on heatwaves owing to a lack of data, she says.

“The message of this report is clear: strong political will is needed to increase adaptation investments and outcomes,” Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Programme, wrote in a foreword to the report.

“If we don’t want to spend the coming decades in emergency response mode, dealing with disaster after disaster, we need to get ahead of the game,” she added.

The COP27 Conference of the Parties (COP27): When Are We Going? What Do We Need to Know About Climate Change?

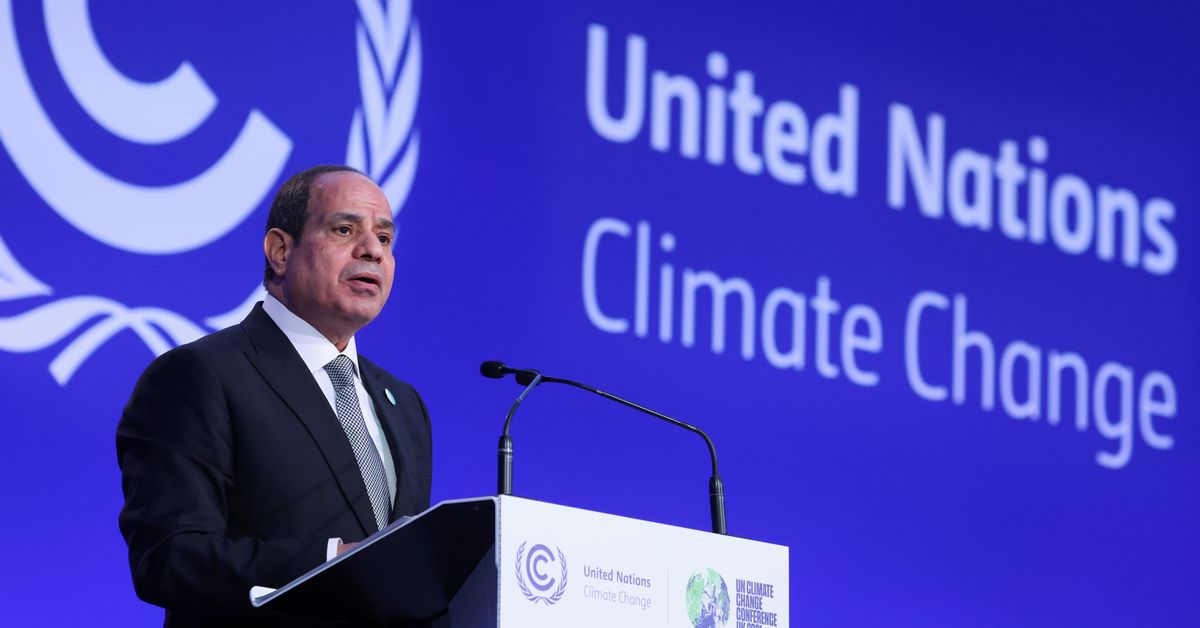

One year later, the math still isn’t pretty. The margin of error was discussed. The next stop on the carousel of global climate talks is between 0.9 and 1.3 degreesC, according to a UN report released just before COP27 begins on Monday. Taryn Fransen, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute and one of the report’s lead authors, says that the stubborn overshoot is disappointing. Since Glasgow, there has been a lot of haggling. Negotiators should be coming back this year in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt, armed with more ambitious promises that they couldn’t make before: Perhaps their country has found a new way to trim methane emissions or to save a carbon-sucking forest or has passed legislation that funds renewables. And yet, despite promises to the contrary, only a handful of countries have pledged more cuts, which together represent only 0.5 out of the 13 gigatons of CO2 scientists say must be slashed by 2030 to meet the Paris goal.

In United Nations jargon, the meeting is called the Conference of the Parties, or COP. The 27th Conference of the Parties meeting is referred to as COP 27.

“The discourse needs to be raised significantly, the level of ambition, so that you can actually continue to do what you’re doing on mitigation even more, but you at the same time meet the adaptation needs,” says Mafalda Duarte, CEO of Climate Investment Funds, which works with development banks like the World Bank to provide funding to developing countries on favorable terms.

Extreme weather all around the world is supercharging as a result of the climate crisis. Look no farther than the deadly floods in Pakistan this summer or Hurricane Ian in Florida this September. Disasters are getting more expensive because humans are burning fossil fuels and swamping the atmosphere with heat-trapping gasses.

Duarte says that failing to spend the money that’s necessary to limit and prepare for climate change exposes the entire world to potential risks. The risks could include armed conflicts, refugee crises, and disruptions in financial markets.

“We have to change our mindset and the way we think, because, actually, when it comes to climate, you know, an investment across borders in other places is a domestic investment,” Duarte says.

Editor’s Note: John D. Sutter is a CNN contributor, climate journalist and independent filmmaker whose work has won the Livingston Award, the IRE Award and others. He recently was appointed the Ted Turner Professor of Environmental Media at The George Washington University. His own opinions are contained in this commentary. View more opinion at CNN.

“Climate change is threatening the very social fabrics of our Pacific communities,” Seru said. This is the reason why these funds are needed. This is a matter of justice for many of the small island developing states and countries such as those in the Pacific.”

The small-island states argued that the polluters should pay for the costs of their pollution.

Other arguments against loss-and-damage payments should be seen plainly for what they are: excuses and stall tactics. The harm is undeniable at this point, as is the cause. Oxfam estimates these climate losses will total $1 trillion per year by 2050.

It has been a long time since the United States took this question seriously. The losses to territory,culture,life and property should be held accountable by the polluter.

We don’t have a lot of wiggle room since the world has already warmed by 1.2 degrees. Staying below that 1.5-degree threshold requires reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades. The world can be transitioned to clean energy in a short time. We could reach a whole new degree of climate destruction if we choose the alternative, including wiping out the world’s coral reefs.

The less carbon we put into the atmosphere, the less risk we put into the climate system — with important consequences for sea levels, storms, drought, biodiversity and so-on.

The Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law (CFI-2017-03), Presented at the Workshop on Possibility of Action and Resolution of Climate-related Claims in a Global Shield

Over the years, many different forms of arguments against action have been taken. The problem was a problem for the future and not the present.

That may feel like a new phenomenon, but it’s been decades in the making. A deadly 2003 heat wave in Europe was linked to human-caused warming. That heat wave killed an estimated 20,000 people.

The onslaught of ever-worsening heat waves, droughts, wildfires and storms can feel both urgent and numbing. The truth is that as long as humans have been burning fossil fuels, we’ve been making the planet more dangerous.

The Fossil Fuel industry is benefiting from hundreds of billion of dollars in subsidies and windfall profits as household budgets shrink and our planet burns.

Loss-and-damage financing could come in several varieties. One possibility, backed by Germany and the V20 group of climate-vulnerable countries, is an insurance-style scheme called Global Shield, along the lines of existing climate-and-disaster insurance. Details are sketchy so far, but if the programme were similar to conventional (general) insurance provision, parties would contribute premiums, creating a pooled fund to provide payouts for damages.

The Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law was formed by the countries of Tuvalu and other small islands. The aim is to explore claims in international courts.

“Litigation is the only way we will be taken seriously while the leaders of big countries are dillydallying,” Gaston Browne, the Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, said last year, according to The New York Times. “We want to force them to respond in a court of law.”

Climate Change: Where we are coming from, where we are going, and how we are preparing for next generation of climate change policy in the 21st century

This is a raging debate, even within the conference. “As it is, The COPs are not really working,” youth climate activist Greta Thunberg, who was a media sensation at last year’s conference, said during an event in London this week after announcing that she will not attend COP27 this year. The COPs are an opportunity for leaders to get attention, using a lot of different greenwashing.

There is a lot of pressure on countries at COP 27 to do more in order to keep the temperature from rising. Since countries agreed last year to strengthen their targets for the year 2030, environmental groups are hoping for more updated national commitments.

The money is supposed to go toward new and improved infrastructure that might help keep people safe in a warming world. That might look like cities designed to be better at beating the heat or communities that are less likely to be wiped out in a wildfire. Enhanced early warning systems that could warn people about flood or storm headed their way is possible. There’s a push this year to secure even more funding for these kinds of adaptation projects, particularly since adaptation costs in developing countries have been projected to reach upwards of $300 billion a year by the end of the decade. When it comes to living with climate change, what it means is different from place to place and people who are most affected are often not included at planning tables.

There are some bright spots. Australia, led by a newly progressive government, doubled its planned cut to 43 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2030. Chile, which is working to transform its constitution into a rights of nature one, is not the only country that has promised more cuts. But most of those updates are from smaller polluters, or from those, like Australia, that are playing catch-up after previously submitting goals that were egregiously lacking in detail or ambition. “A lot of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked,” Jansen says.

At last year’s meeting, world leaders agreed to transition away from fossil fuels and cut greenhouse gas emissions more quickly than in the past. But they failed to make substantive promises about how that would happen.

Fransen is in charge of keeping track of all those emissions plans and whether countries are sticking to them. It is difficult to take stock. For one thing, it means actually measuring how much carbon nations emit. It also involves showing the effects those emissions will have on the climate 10, 20, or 100 years from now.

Unfortunately, it isn’t easy to determine how much CO2 humanity is producing—or to prove that nations are holding to their pledges. There is a lot of gas in the atmosphere which muddys the origin of each signal. Natural processes release carbon, like decaying vegetation and thawing permafrost, complicating matters. Think of it like trying to find a water leak in a swimming pool. Researchers have tried pointing satellites at the Earth to track CO2 emissions, but “if you see CO2 from space, it is not always guaranteed that it came from the nearest human emissions,” says Gavin McCormick, cofounder of Climate Trace, which tracks greenhouse gas emissions. We need more sophisticated methods. For instance, Climate Trace can train algorithms to use steam billowing from power plants as a visible proxy for the emissions they’re belching. The scientists have been using weather stations to get a better idea of emissions.

The Case of Anopheles stephensi: Malaria in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia, is not a Vaccine Silver Bullet

Models suggest distributing COVID-19 vaccines more fairly might have saved more than a million lives in 2021. Plus, how to decarbonize the military and what to look out for at COP27.

evaluation, assessment and accountability will be the main focus. Climate- policy analyst David Waskow says we can’t just move on with new commitments without knowing whether current commitments are being carried out.

The progress towards eliminating malaria in Africa is at risk because of mosquitoes that are not killed by pesticides. In a study in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia — the site of a malaria outbreak — Anopheles stephensi accounted for almost all adult mosquitos found near the homes of participants with the disease. The notorious species can breed in urban environments and persist through dry seasons. It could infect more than 100 million people in Africa if they are not protected by vaccines and other control measures. But “there is no silver bullet” for this fast-spreading vector, says molecular biologist Fitsum Tadesse.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03572-0

How should the militaries of the world play a role in global carbon emissions? A warning to the Egypt-based COP27 climate conference

The US military puts out more CO2 per capita than every nation in the world. But militaries are largely spared from emissions reporting. Eight researchers outline how to hold militaries to account in the global carbon reckoning.

“Imagine making a data-driven plan for the world, but leaving out more than one billion people in Africa,” writes energy researcher Rose M. Mutiso. That is the frightening truth behind net-zero emissions proposals. She argues that we can’t we can’t engage meaningfully with the concept of net zero — at COP27 and in general — without Africa-specific data, appropriate models and African expertise.

After a stint at Google, astronomer Oliver Müller is back in academia — and he has learnt some valuable lessons. Don’t be a hero. “If a task can be finished only through putting your mental health and even physical health at risk, you are effectively hiding flaws in the system.”

The leaders of wealthy nations are warned by the hosts of the upcoming climate conference in Egypt that they will not be able to backdrop on commitments made in Glasgow last year.

Mahmoud Sakr, president of the Egyptian Academy of Scientific Research and Technology in Cairo, says that scientists from climate-vulnerable countries will be urging COP delegates to boost research funding. He says that countries need to conduct more climate studies in the Middle East and North Africa, where low rain and arid conditions exist. The analysis states that the Arab world accounts for just 1.2% of the published climate studies.

In 2015, Egypt estimated that it needs to set aside $73 billion for projects to help the country mitigate climate change and adapt its infrastructure. The number now is more than tripled according to the environment minister. “Most climate actions we have implemented have been from the national budget, which adds more burden and competes with our basic needs that have to be fulfilled.”

Will the COP in Africa be remembered? A warning from Mitchell on loss-and-damage finance in the high-income world, says Adil Najam

Ian Mitchell, a researcher with think tank the Center for Global Development in London, warned of possible unintended consequences if agreement on loss and damage becomes a deal-breaker at the meeting. It would not be new money if the high-income countries agreed to the principle and absorbed loss-and-damage finance as part of their humanitarian-aid spending.

I think that these issues will probably be solved in Egypt but the politics will probably get messy, says Adil Najam, who studies international climate diplomacy at Boston University. He adds that loss-and-damage finance can no longer be avoided by the high-income countries, especially given that climate impacts in vulnerable countries are becoming much more visible and severe.

Fouad says that organizing this year’s COP in Africa has been transformative. We are expecting more attention to issues that are important to us Africans, such as food security, desertification, natural disasters and water scarcity. This COP is a chance for more African youth, non-governmental and civil-society organizations to be heard.”

Khan’s hometown was underwater. A woman walking barefoot with a sick child was saved by a friend who was out in the floods. Khan’s mother couldn’t go to her hometown to check on her daughter because of washed out roads.

Loss and Damage: The Need for Reparations in the Developing World, Not the Promise of a Climate Fund: A Viewpoint from a Former Top US Climate Official

The South Asian country is responsible for less than 1% of the world’s planet-warming emissions, but it is paying a heavy price. And there are many other countries like it around the world.

Rich countries like the United States have bridled at agreeing to a loss and damage fund, fearing they could be sued.

There is only so much time left for a dedicated loss and damage fund in developing nations, and Pakistan’s cascading disasters are indicative of that, according to a former top US climate official.

Gina McCarthy said that the developing world is not prepared to protect themselves from climate disasters. “It’s the responsibility of the developed world to support that effort. But they are not being delivered.

As a concept, loss and damage is the idea of rich countries paying poorer countries that have been damaged by climate disasters they did not cause.

He said that rich nations are dragging their feet. He said that it was important for them to take responsibility.

“‘Reparations’ is not a word or a term that has been used in this context,” US Climate Envoy John Kerry said on a recent call with reporters. He added that the developing world needed the aid of the developed world in dealing with the effects of climate change.

Kerry has committed to having a conversation on a fund this year ahead of a 2024 deadline to decide on what such a fund would look like. And US officials still have questions – whether it would come through an existing financial source like the Green Climate Fund, or an entirely new source.

Kerry caused a controversy at a New York Times event when he suggested that there is not enough money in the world to help Pakistan and other countries recover from climate disasters.

“Look at the annual defense budget of the developed countries. “We are able to mobilize the money”, said a senior associate at E3G. It is not a question of money being there. There is a question of political will.

“Do we expect that we’ll have a fund by the end of the two weeks? I hope, I would love to – but we’ll see how parties deliver on that,” Egypt ambassador Mohamed Nasr, that country’s main climate negotiator, told reporters recently.

But Nasr also tamped down expectations, saying that if countries are still haggling over whether to even put loss and damage on the agenda, they’re unlikely to have a breakthrough on a financing mechanism.

He believes that the loss and damage conversation may continue over the two weeks of Sharm, perhaps ending the framework set for a financing mechanism or clarifying whether funds might come from new or existing sources.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2022/11/07/world/loss-and-damage-explained-cop27-climate/index.html

Whats at stake at the global climate negotiation? The case of the United States and the Ukraine, which was inspired by the Russian invasion of Ukraine

“For countries not on the front line, they think it’s sort of a distraction and that people should focus on mitigation,” Avinash Persaud, special envoy to Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, told CNN. “If we had done mitigation early enough, we wouldn’t have to adapt and if we’d adapted early enough, we wouldn’t have the loss of damage. We have not done those things.

Since then, there have been some big geopolitical changes. This year’s meeting will be overshadowed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The invasion further complicated relations between the world’s largest economies and caused havoc in the fossil fuel markets. The war has made many countries even more dependent on coal-fired power plants for their electricity, which are the most harmful source of greenhouse gas emissions.

But there have been positive developments as well. Wind and solar are the fastest growing renewable energy sources. The International Energy Agency predicts that global demand for all types of fossil fuels will peak by the mid-2030s.

China and India, the two biggest emitters, will raise emissions until at least 2030. They’ve argued that fossil fuels are needed to support their growing economies.

Scientists warn that decades of sea level rise, extreme heat waves and storms are unavoidable because of how much global temperatures have already risen. That means billions of people will need to adapt to a hotter Earth.

But limiting emissions could avoid some of the most extreme impacts, like much more deadly heat waves, more flooding in coastal cities due to sea level rise and the loss of almost all coral reefs.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/11/07/1132796190/faq-whats-at-stake-at-the-cop27-global-climate-negotiations

A UN Secretary-General’s Call for Rich Countries to Pay Their Share for Climate Change Problems and the Challenge It’s Asking for

They argue that wealthier nations should pay for the problems they caused, including the cultural losses that happen when towns and villages must relocate. So far, wealthier countries have agreed to keep discussing it, but haven’t committed to providing new funding.

Huge investments are going to be required. There’s no way to escape it. There is more money to be made eliminating emissions from the global economy. The cost of not dealing with this problem could be very high.

In the United States alone, quickly cutting carbon emissions could grow the country’s economy by $3 trillion over the next 50 years, says Deloitte, the consulting firm. There is a chance that not responding to climate change could cost the US $14.5 trillion in the next 30 years.

It’s crucial that poor nations are kept on board with efforts to cut emissions by making good on that promise. But they also say that $100 billion is just a fraction of the money the developing world is going to need.

The findings could inform the way in which strategies that help countries to adapt to extreme heat or heavy rainfall are implemented. The economic effects of five hot days of the year imply that those few days have really outsized effects. Investments designed to minimize the effects of heat extremes in the hottest part of the year would deliver major economic returns.

According to a climate scientist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, the study emphasizes the need for rich nations to pay their fair share. “Given the unequal burden and the share of historical emissions … the global north needs to support the global south in terms of coping with these adverse effects.”

The UN Secretary-General did not mince words when he spoke. “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator,” he warned.

He also referenced the fact that the global population is expected to officially hit 8 billion people during this climate meeting. “How will we answer when baby 8-billion is old enough to ask ‘What did you do for our world, and for our planet, when you had the chance?’” Guterres asked a room full of world leaders.

Extreme storms and floods are related to the climate, so the UN wants people to be aware of that. It’s called Early Warning for All.

The new plan calls for $3.1 billion to set up early-warning systems over the next five years in places that don’t already have them, beginning with the poorest and most vulnerable countries and regions. More money will be needed to maintain the warning systems longer-term.

The Barbade Islands Climate Crisis: Implications for the UN Convention on Biodiversity, Climate Change, and the Sustainable Future of Low-Income Countries

The prime minister of the island ofBarbade went a step further in her opening speech. She called out corporations that profit in our fossil-fuel intensive economy, including oil and gas companies themselves.

Those corporations should help pay for the costs associated with sea level rise, stronger hurricanes, heat waves and droughts around the world, she argued, and especially in places like her nation that are extremely vulnerable to climate change and don’t have the money to protect themselves.

The US government is working with AT&T to provide free access to data about the country’s future climate risks. Community leaders should better understand and prepare for local dangers from more extreme weather.

The Climate Risk and Resilience portal will give information about some of the hottest and most changeable conditions. Additional risks such as wildfire and flooding will be added in the coming months.

More than two dozen countries say they’ll work together to stop and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030 in order to fight climate change.

More than one third of the world’s forests can be traced back to 26 countries and the European Union which are part of the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership.

More than 140 countries agreed last year to conserve forests at the 26th Conference of the Parties. The United Nations said that there is not enough money being spent to save forests that capture and store carbon.

Many LMICs would rather see high emitters accept liability for their historical emissions and agree to provide compensation for damage wrought. This third option is by far the most contentious for high-income countries. They argue that attribution studies cannot yet determine whether climate damage in one country can be traced to specific emissions from another. They also fear that it could lead to trillions of dollars in claims. As a compromise, the COP agenda item agreed ahead of the meeting explicitly excludes questions of liability and compensation. But some LMICs will probably fight hard to have them discussed.

Egypt will play a role in finding a way forward. Pakistan (one-third of which was under water in September because of flooding) also has a pivotal, although tricky, role: it holds this year’s presidency of the G77, the largest group of LMICs, which also includes China. There is a group not on a single model.

It might prove instructive to examine the experience of negotiators on the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The delegates working on the climate convention have been more willing to discuss rules for liability and compensation. Take a biodiversity agreement called the Cartagena Protocol, which concerns the international transport of genetically modified (GM) organisms, signed in 2000 after a multi-year negotiation. African countries, led by Tewolde Berhan Gebre Egziabher, head of the Ethiopian environment agency, were determined to include a provision for liability and compensation if these organisms caused harm. This idea was opposed by some high-income countries, led by the United States, on the grounds that there was no or little evidence that GM organisms could be harmful. The provision was not included because it was endangering the whole treaty. The liability and compensation rules of the UN-convention were adopted by member states in 2010.